Steve Brodner visited us a couple of months ago and paid such careful attention to the community. He published what follows (in a much nicer way) in the May, 2005 Texas Monthly.

An Artist's View of the Border

Impressions gathered by Steve Blodner

Tuesday, April 26, 2005

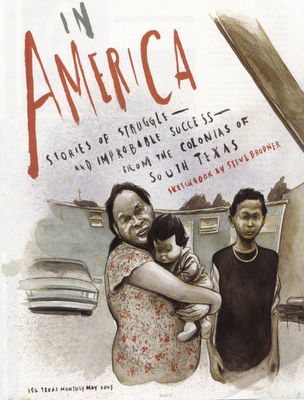

ALONG THE TEXAS BORDER running between El Paso and Brownsville there are some 1,500 colonias: rural, unincorporated, and often poverty-stricken communities where immigrants have bought inexpensive lots and settled in for their first taste of the American dream. This winter I traveled to a handful of these communities, a few of which have existed now for more than four decades, to compile a portfolio of drawings that would tell some of the stories that make up the colonias' experience. While I encountered many families living in deplorable conditions, I also witnessed countless acts of near-miraculous transformation. With the help of unions and churches, many of the residents I visited were wielding their political power for the first time and slowly creating a better existence--sometimes brick by brick--for their families.

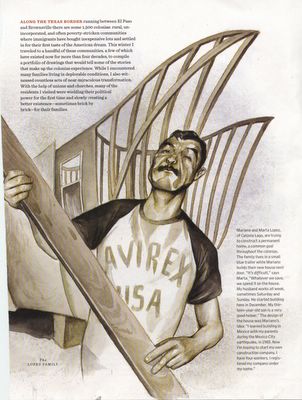

Mariano and Marta Lopez, of Colonia Lago, are trying to construct a permanent home, a common goal throughout the colonias. The family lives in a small blue trailer while Mariano builds their new house next door. "It's difficult," says Marta. "Whatever we save, we spend it on the house. My husband works all week, sometimes Saturday and Sunday. He started building here in December. My thirteen-year-old son is a very good helper." The design of the house was Mariano's idea: "I learned building in Mexico with my parents during the Mexico City earthquake, in 1985. Now I'm hoping to start my own construction company. I have four workers. I registered my company under my name."

Some colonias residents, such as Pedro Rangel, who has lived in Cameron Park since 1965, have experienced the strength of political action firsthand: "Back in the sixties, there was no water, no sewers, and no streets. If it rained, you were not getting out, unless there were six people pushing your car. Things started to change about seven years ago. Before, nobody knew what voting was all about. People said, 'What for? Nothing will change.' We learned how much power we had. Politicians said, 'Well, there are nine hundred people voting in Cameron Park. Let's hear what they've got to say.' As soon as we started voting, we got the paved streets, water, and sewers that we had been denied. They listen to us now."

Ernesto Cortes, the Southwest regional director of the Industrial Areas Foundation, has been supervising the I AF's organizing in the colonias for the past three decades: "Valley Interfaith started working with residents in Las Milpas [outside of Pharr]. We saw that the real leader there was a lady named Carmen Anaya. One day she pointed out to a political figure that kids couldn't go to school because of a lack of drainage in the area. [The politician] would not walk in the area where the children had to walk every day to go to school because he didn't want to get his boots muddy. Carmen was furious. She came to a new realization: 'I used to work for candidates until I understood that they had to work for us.' She saw the power that was created because of the organizing Valley Interfaith was doing."

Changes really started happening in the colonias when the politicians began to pay attention. Elizabeth Valdez, the lead organizer for Valley Interfaith, a network of more than forty churches and schools that helps organize residents along the border, showed me a picture of Senator Kay Bailey Hutchison's visit in 1994. "This is her at a colonia in Mercedes. It was raining that day. She slipped in the drainage ditch but didn't go all the way down. The roads weren't paved, and it was slush, mud, and water."

Finding ways to keep kids in school is another local challenge. Cathy Thomas is the principal at Guadalupe Regional Middle School, in Brownsville: "The struggles these kids go through are personal ones. They worry a lot. They worry about the fact that their parents have not been able to pay rent for three months and the landlady will kick them out. We have a girl whose father entered the country illegally, and he's now in prison. The mother doesn't drive, and one of her children is ill. This girl is worried all the time."

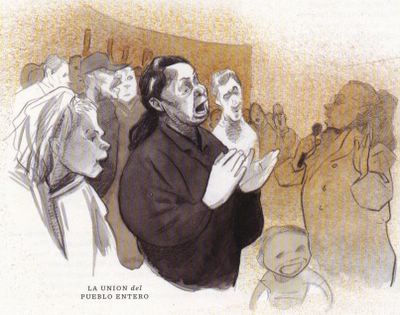

One day I went to a meeting of the nonprofit group La Union del Pueblo Entero (the Union of All the People), which helps connect colonias residents with social services. Residents met with an attorney who helped with tax questions and a representative of Wells Fargo bank, who outlined a program that offers low-interest credit cards for those with a LUPE membership. "I grew up in a colonia without water," says Juanita Valdez-Cox, LUPE's director. "In a colonia, I see people that have a one-room house and they have, say, a dirt floor. But that same family is already thinking about how to have a house with a real floor. I remember my father saying, 'I want you to have a better life than the one we had.' It was poverty, but it wasn't the kind of poverty that completely engulfed you and made you give up and say, 'Okay, this is the way I'm going to be forever.' There's a lot the government can and should do. But all programs here depend on self-help."

Many residents organize through their church to get their message out. Father Alfonso Guevara is a pastor at St. Joseph the Worker Church, in McAllen: "We take government officials down to the colonias, and we educate them on who they're supposed to be representing. We say, 'Congressman. Senator. Walk with us.' They can see the conditions at their worst. There's a level of respect that a politician has in dealing with members of a congregation. Because it's a church community, the organization has staying power. This kind of organizing is very important in campaigns for getting out the vote. In the last election, one of our precincts had the second-highest turnout in the city of McAllen. This parish organized the people and, with other churches, changed the city. Valley Interfaith has a phrase: 'We make private pain public.' That is the source of our energy."

Ron Tupper is the chairman of the Milagro Clinic, in McAllen. He says lack of access to health care means unnecessarily harsh cases in his emergency room. "The chronic problems are not diagnosed and get compounded and get complex because people can't see a doctor. These are things that wind up in the emergency room. They're totally preventable." Tupper Is planning to use homeland security funds to purchase large high-tech medical , vans that can be sent into colonias to work as rolling clinics.

Some residents oven leave the country to obtain medical help. "When I need health care, I go to Mexico," says Maria Elena Morales, who lives in Colonia La Mesa, north of Mercedes. "My mother is diabetic. We take her to Mexico every month. It costs $150. It's a ten-to fifteen-minute drive. I take my daughters there, even though they get Medicaid. Doctors here won't prescribe everything they need."

Ninety-four percent of the residents of Hidalgo County have no health insurance, and the statistics are similar throughout the colonias. The recent cuts in children's health care funding have only made the situation worse. At the emergency room in the McAllen Medical Center, sometimes the wait lasts up to seven hours.

For many kids, the military is seen as the best way to get ahead. "I got my ROTC diploma," says Luis Quintanilla, an eighteen-year-old high school senior from Colonia East Indian Hills, in Mercedes. "But I'm not sure about joining. Recruiters tell me that if I join, they will help me with my citizenship. The Marines have called me two times." (In fact, the military cannot assist with immigration status for its recruits.) Marist Father Mike Seifert, of the San Felipe de Jesus Catholic Church, in Cameron Park, is tired of seeing so many recruiters in the schools: "Every day the students see them at the high

school. They call every kid once a week. Recruit and recruit and recruit. And after they're in the Army, you see them stripped of their engagement, the spark of life. They trade that spark for sitting up straight." There are now roughly 41,000 legal aliens in the U.S. military. "We went to a high school the other day," says Sister Sanchez, "and there were about one hundred names on the wall-our parishioners in the armed forces. Every church has an altar with the pictures and names. The Rio Grande Valley has the highest percentage of soldiers who have been killed. About ten percent of the soldiers who

have gone to war have come back in body bags."

Maria Guadalupe Sanchez, of Cameron Park, is a data collector for the University of Texas at Brownsville. She grew up in Matamoros and then moved with her husband in the eighties to live in a trailer in Texas and work as a migrant worker. "There was no light," she says. "A neighbor would run an electric cord past one trailer through to the other. One house gave water to fifteen people." She and her husband, Sergio, finally moved into a new home in 1998. Sergio works for Amfels, an oil rig builder, and one of their daughters dreams of going to medical school.

Not all the stories that I encountered had a happy ending. Blandina and David Ibarra and their four children live in Cameron Park in a dilapidated trailer that offers almost no protection from the elements. Since David lost his construction job, they've been unable to build anything new, and the children share a tiny room that doubles as a space for storage. "My children confront me, questioning, 'Why did we come here?'" says Blandina.

In 1968 Ramona Gonzalez, here with her grandson, moved into a house so small that her eight children had to sleep on the floor. For years they put all the extra money that the family earned as migrant farm workers aside to build a home in San Juan. The work was always hard; sometimes a five-gallon bucket of tomatoes would yield only 20 cents. But after twelve years of unflagging devotion to their plan, Ramona and her husband, Anastasio, have a fine home. They have also seen five of their children graduate from college.

There are few places in Texas where residents are so united by a common struggle. Father Seifert says this is one of the aspects that make the colonias special: "What is in the colonias that's of value to the rest of our American community? The sense of community continues to be of value. But it's not a gated community. Here you are a part of something bigger than yourself. You're not anonymous. There's a sense of purpose about things." He tells me about the tragedy that befell the Alvears, a family of seven who lived in a ramshackle trailer without wiring in Cameron Park: "The kids were sleeping on the floor because it was hot as blazes. They had an extension cord under the rug, and it caught fire. The mother and father each pulled a daughter out of the smoke-filled trailer, but when they tried to rescue their small son, Emmanuel, who could not reach the latch on the door that closed behind them, the propane tank exploded. The mother and one girl were horribly burned. Emmanuel was killed." Today the Alvears live in an attractive brick home that stands on the same site. It was the neighbors who got together and provided the materials. On the right wing is a small shrine to Emmanuel.

Argelia Lopez homesteads with her family in El Falco, a new colonia near Mission. “The first thing I want is for the kids to get a good job. Construction is not steady. My son says, ‘One day, I’ll build you a big house.’ I say, ‘Yes, that that’s your dream.’ They say they won’t get married until I’m taken care of. They know how hard we struggled.” She points to the trailer next door. “Everybody helps here. A neighbor’s trailer burned down two weeks ago. The neighbors all got together, sold plates of food at the church, and raised money to help her out.”

For Teresa and Inocente Barrera, the American dream is close to a reality. They moved to Colonia El Jay in 1985 and raised a family while riding out the colonia’s roughest times. "Originally, there was no water, no phones, no street," says Teresa. "Just dirt. When it rained, the cars would get stuck. There was one water faucet for the whole colonia. So I and other housewives from El Jay would go together to the county commissioners. 'If you pave the roads, then the school buses will come,” we said. They said, 'You'll have to wait.' We kept having the meetings and seeing the commissioners. We would call, write letters. We got potable water in 1987, and in 1994 they finally fixed the streets." The Barreras have been married for 46 years, and they have eight children. Two of them are teachers and one owns a construction business. Their four sons, Silvestre, Ramiro, Fidencio, and Antonio, have their own houses (shown below) within sight of their mother and father's. Antonio, a tractor salesman, followed his parents' example. "It took me five years to build the house," he says. "A lot of people, when they get the tax refund, they buy cars or take vacations. We put it into the house and looked for sales on materials. When we first came here with Dad, it was still hard living here. This life teaches you discipline. It wasn't a difficult life, because we appreciate what we have. It helps to have people who don't ask for things but work for what they have. A family makes a big difference. You have to think about your family."

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)